This is the draft of what was meant to be my first post with a publication that I ended up not working for. I didn’t get a chance to send it to my editor before I was let go, but I have decided to publish it and other pieces that never saw the light of day. This is the first of these publications.

The internet makes us telepathic, angry, and weird. To cope with this we need to learn the math behind how it does that, and we can start with the view count of a few music videos on YouTube.

In 2011 Katy Perry released Last Friday Night (T.G.I.F.). Last Friday night was a successful pop song with a video that paid homage to John Hughes movies and teenage life. Last Friday Night was a global success and it has been viewed over a billion times on YouTube. In 2012, a parody of Last Friday night was created by fans of the open world-style video game Minecraft. Called Don’t Mine at Night, the song’s video featured 3D-animated Minecraft characters singing and dancing about the in-game danger of being killed by a monster if you mine during the night. A year later in 2013, fans of Minecraft and the Hasbro animated show My Little Pony (Which has a surprisingly large adult fanbase) created another parody of the last parody also called Don’t Mine at Night, turning the admonition in the Mincraft song into a sweet love song from one fan-created character to a regular character from the show. All that is a typical internet rabbit hole, but here’s the important part: as of this writing, Don’t Mine at Night (Pony Parody) has been viewed 54 million times. (2023) That’s more watches than there are people in Spain. It’s catchy, and well animated, but the amount of insider knowledge required to understand this video should be too much. One might reasonably ask how millions of people could be enthusiastic fans of a simplistically rendered open world game, an animated pony show intended for pre-teen girls, and Katy Perry. The story of that song is amusing enough, but the wider phenomenon that Don’t Mine at Night (Pony Parody) reflects has crept largely unnoticed into global politics and culture. You see it in the rise of European fascism, and the American Alt-Right. It’s there in the #metoo movement and the Tunisian Arab Spring. It’s part of statistical mathematics, where it has a name: The Law of Truly Large Numbers.

In statistics, the Law of Large numbers tells us the outliers tend to revert to the mean. In plain language, this means that over time, things average out. Large numbers is why you’re probably never going to win the lottery — generally we all live at the mean the majority of the time, by definition. But when those numbers get large enough, Truly Large, you will be able to find just about any possible outlier, which is why a woman named Joan Ginther won million-dollar amounts in lotteries four times. There isn’t really a secret or mysterious force here. The math says that most people who play in lotteries will lose, and sometimes an outlier will win multiple times. That’s just the natures of Large Numbers, versus Truly Large Numbers.

Most internet-fueled popular movements, be they good or bad, arose from the same effect of large numbers: in 7.6 billion people, (8 billion in 2023) more people agree with you than you can possibly know in your lifetime. According to the anthropologist Robin Dunbar, a person can only probably know about 150 people in their lifetime, in any emotionally or intellectually significant way. Some people think that number is a bit higher or lower, and it probably depends on the person, but no one who studies social network and human relationships argues about the order of magnitude on how many people a single person can really know. This is trivially true for anyone — you know very well that your 5,000 Facebook friends are not friends in any way that involves deep knowledge and investments of time and energy. There’s just not enough hours in the day, or days in a lifetime.

If you hold a one-in-a-million opinion, there’s 7,600 people who are right there with you. In a species capable of maybe a couple hundred meaningful relationships, 7,600 might as well be 76 thousand, or 76 million. It’s like standing in the middle of a crowd of 1,000 or 100,000 – it feels the same from when you’re there, surrounded by the press of bodies on all side.

None of this is new, it’s been part of the human condition since we left small tribes behind for civilization. What is new is the network effects of discoverability, recruitment, and community, built around subcultures and minority opinion which you could have never found before the internet came around. Understanding this not only explains the breakdown of consensus reality, but helps you choose and check your realities more reliably.

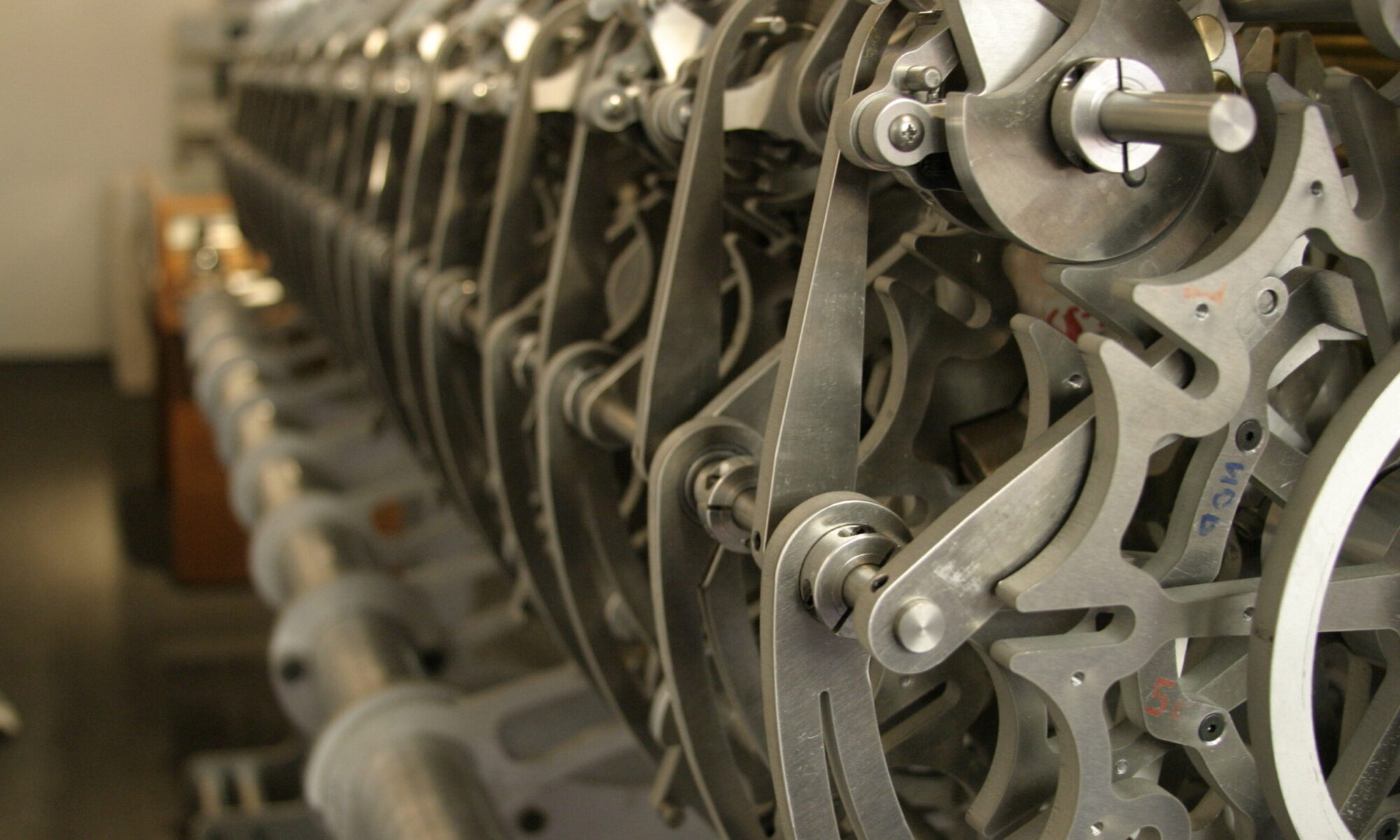

Directories, search engines, social media algorithms, and indexes are mechanisms for defeating the Law of Large Numbers, which says in a huge internet you will never find the thing that’s relevant to you — the thing you want. But they manage it by thrusting you into the realm of Truly Large Numbers, where you can be, and often are, surrounded entirely by outliers. A google search results chooses from billions of options to ten on the first page, hiding the enormous world of variations, counter-factuals, and the diversity of thought that didn’t make that first page cut. Google’s job is to make sure you win the information lottery on every search, and never know how unlikely it was.

If you’ve been told all your life that the Earth was a globe, but it just has never felt round to you, that thought was not likely to go anywhere before the Information Age. Talking about it in your local community was likely to lead to social isolation, and without support from a friend, there’s not much in the world to confirm it. These ideas come up in people’s minds all the time, but without reinforcement, they tend to fade away in favor of social consensus. That changed with the internet, for both good and ill. In the age of global forums and search engines and social media, a quiet inquiry from your own home, with no risk of getting ridiculed by friends or family, could put you in touch with more people who feel like you do than you could imagine meeting in dozen lifetimes. Not only is that feeling reinforced, but it’s celebrated in new friendships. Suddenly you’ve gone from someone with a few doubts about the roundness of our collective home to someone who is invested. You will lose friends and community if you start to suspect the data points to the Earth being round after all. You may come to think that the revolution that will bring NASA down could begin any day, because there are so many people like you. You may even find others and recruit them to the cause, now more emotional than practical for you. And all this can happen without anyone involved realizing that the way large numbers work, so unintuitive to the human mind, means everyone you know or could ever know are no more than drops, drowned in a sea of people.

You can take that same concept, and apply all its parts to sexual assault against women in the workplace instead of science denial. Add a hashtag — #metoo — and maybe you discover that enough of the drops in the sea of people are with you that you can expose a world of hidden abuse. With that exposure, just maybe the tides of culture start to shift, even if just a little. But from any particular point on a network of billions, it’s impossible to predict with any precision how far and how fast ideas will go, or sometimes even if a community people are being drawn to is righteous or not. For most people, being accepted is more important than the righteousness anyway. We want to be friends, not saints.

The network discoverability that traps us in strange idea bubbles, due to the effects of Truly Large Numbers, is something we’re going to need to educate against, consider with policy, and perhaps even address within our networks. There is no one answer, because the network itself sorts without knowing what is weird. Flat earthers or lizard people conspiracists don’t look any different to computer-mediated discovery systems trying to match people with communities than bone cancer researchers or urban hydrologists. They’re all niche, and that’s the main thing the network “knows” about them. The infrastructure doesn’t editorialize, and we don’t want it to.

We remain social creatures who evolved and developed culture without an internet messing with our mathematical and social intuitions. But we have an internet now, and we need to develop new intuitions through mathematical and internet literacy education. The internet is made of people and their ideas, and it doesn’t get better until those ideas get better.

There’s an easily overlooked but incredibly important scene in the 2018 movie, “Ready Player One”, which is based in and around a fictional virtual reality known as the Oasis. The Oasis avatar of one of the central characters, Aech, is trying to ‘warn off’ the avatar of the story’s main protagonist, Parzival, who is considering meeting up with the avatar of a ‘new friend’, Art3mis. Back in Aech’s ‘virtual lair’ in the Oasis, Parzival is fussing over what virtual outfit to wear for the encounter…

Aech: “Buckaroo Banzai?”

Wade: “Yeah…”

Aech: “Really? You’re gonna wear the outfit from your favorite movie? Don’t be that guy!”

Wade: “I am that guy…”

Aech: “Zee, you gotta be more careful about who you meet in the Oasis!”

Wade: “Aech, Artemis gets me. She’ll get my outfit. There’s just this connection. I mean, sometimes, we even…”

Aech: “Finish each other’s sentences?”

Wade: “Yeah!”

Aech: “*We* have that… Me and you.”

Wade: “Yeah, I know, but that’s because we’re best friends, Dude.”

Aech: “She could be a dude too, dude!”

Wade: “C’mon!”

Aech: “I’m serious! She… could actually be a 300lb man who lives in his mother’s basement in suburban Detroit. And her name is Chuck.”

That exchange captures, for me, the reality of the modern internet. Most of what is there is not what it seems. Everything you so eloquently right here is true… but I think there are at least two other dimensions that have come in to much sharper focus since about 2015. Or, perhaps, two other groups are active on the internet that have an out-sized effect on all other users.

The first group are the trolls; people of a sadistic persuasion who derive significant and perverse pleasure from “messing with other peoples’ heads”. When we think about the QAnon movement in the United States, in particular all the ‘false prophesies’ of when some momentous event will happen, there are more than enough examples for us to superficially believe that the movement would have run out of steam by now. But it hasn’t. This is because it is being constantly fed by an army of existing and new trolls, who join the message boards and the conversations for the sole purpose of seeing just how far their lies can propagate. (Anyone else remember that annoying trend of ‘don’t break this email chain’ from the 80s and 90s?). And we really musn’t dismiss this as a fringe/nutter thing – remember the gunman who burst in to a pizzeria because he was convinced that a cabal of Satanist, cannibalistic Democrats were sacrificing children in the basement? When you read it here, it sounds ludicrous. Because it is. Didn’t stop someone from falling for it and taking up arms to respond…

The second group are the actual malicious actors. Whether we’re talking about the so-called “heart-breakers” – people who claim to be women in order to snare lonely, vulnerable men and trick them in to sending money; or whether we’re talking about state-sponsored actors like Russia and North Korea, who operate massive troll-farms in order to create exactly the sort of division we see playing out in the United States at the moment… for every one example of someone managing to connect with another group of “fringe thinkers”, as described by Quinn in the article, there is at least one (likely more than one) vulnerable person who becomes a victim to manipulation of the sadistic or criminal kind.

As I’ve commented before: the internet is an amplifier – a very powerful, indiscriminate one. It takes all that is good and all that is bad about human nature and adds a nought, multiplying it by an order of magnitude.

And a big part of the challenge/problem is an aspect of human nature that is as inseparable from us as the brain in our bodies: the instinct to survive that kicks in when we are hurt. Unfortunately, that instinct triggers every bit as well when the pain we feel is emotional. But the “abstraction” of the internet brings a new and potentially dangerous dimension to that recoil, that lashing out.

If a person physically strikes you and you are hurt by the blow, you might strike back. You feel the energy you put in your counter; you feel when it hits the target and you can see or hear or feel the pain you cause. That reflexive, defensive part of your psyche is ‘satisfied’. Tit for tat. You hit me, I hit you back.

That doesn’t work on the internet.

Researcher Albert Mehrabian found that, in face-to-face communication, 55% is non-verbal, 38% vocal (tone) and only 7% derived from the actual words themselves. That means that as you’re reading this comment, you are only receiving 7% of what I am trying to transmit.

As a consequence, when communication over the internet involves (unconsciously, maliciously, defensively, reflexively or otherwise) something hurtful, the chances of us being completely unaware of the pain we inflict is quite high. Which means that if you are doing this maliciously – and if you want to see a reaction, to ‘get your kick out of it’ – then you are going to be far, far more aggressive than you would need to be in real life. You ‘add a nought’ and dial up your venom, because you want the gratification of seeing a reaction, but to get that you are going to have to write something *so* vicious that I lose control and show you the hurt when I respond. In face-to-face arguments every day, people get hot under the collar and vent their frustration, but then, more often than not, they calm down. That doesn’t happen on the internet, because there is no immediate feedback; we don’t see the reaction; attackers don’t get the confirmation feedback that ‘they have been heard’. So they keep on attacking.

So the internet amplifies, again, without us being aware it is happening.

Even if the internet were only used by people with ‘genuine misguided intent’ – like the Flat Earthers – then it would be a dangerous, difficult place. But add in the growing awareness from the range of malicious actors out there that it can be ‘so much more’ and you have something significantly more serious.